The First Malay Book in Europe

THE FIRST MALAY BOOK IN EUROPE

written by Rozan Yunos

published in The Brunei Times on Sunday, February 17, 2013

IN THE 16th century, European travellers and traders started arriving en masse at Southeast Asian trading ports. They wrote about the cities and the peoples whom they encountered.

Many of the descriptions about Brunei were derived during this period. Among the famous travellers was Antonio Pigafetta, the Italian chronicler who arrived in Brunei as part of Magellan's voyage circumnavigating the globe. Pigafetta's descriptions of Brunei are most often quoted nowadays. There were other travellers as well who were here in Brunei such as the Spanish, the Portuguese and the Dutch. The British and the Americans came much later.

Malay was then widely spoken in the region. In the 15th century, during the Malacca Sultanate, Malay was used as the regional language, a sort of lingua franca in the Malay archipelago. Malay was spoken by both the locals who live in this region and also by the traders and artisans that stopped and traded at Malacca using the Straits of Malacca. Around the Borneo Island and around the islands of southern Philippines and perhaps the northern Philippines, Malay must have been used as well.

Amin Sweeney in his book "A Full Hearing: Orality and Literacy in the Malay World" (1987) noted that European writers of the 17th and 18th centuries such as Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1605-1689), Louis Thomassin (1619-1695) and John Werndly (1656-1727) were describing the Malay language as the "language of the learned in all the Indies, like Latin in Europe". The Dutch scholar, Francois Valentijn (1666-1727) also described the use of the Malay language in the region as being equivalent to the contemporary use of Latin and French in Europe.

With the Malay language so widely used in Southeast Asia, many wondered how these Western traders communicated with the natives of Southeast Asia at that point in time.

Obviously, the first Europeans who arrived returned back with notes and perhaps compilation of vocabularies to help other latter traders.

Some perhaps had their own Malay interpreters among their crew. According to Donald Lach in the book "Asia in the Making of Europe: Volume II: A Century of Wonder Book 3" (1998), among the crews working for Magellan was a native Malay slave from Sumatera who Magellan had brought back to Europe much earlier. He was known as Henrique. When Pigafetta was in Brunei and in Southeast Asia, he had at his disposal this Henrique who was able to help him communicate with the peoples of Southeast Asia then.

However what probably helped the latter European traders was that a number of these notes and vocabularies collected and compiled by the early European traders were actually printed and made available to them.

Sir Francis Drake was the second person after Magellan to circumnavigate around the world. His squadron consisting of five vessels left in December 1577, and returned in September 1580 with only one vessel completing the journey. However, despite that setback, Sir Francis Drake's companions managed to compile a list of 32 Javan words with their English meanings. The compilers also provided a list of the "Kings or princes of Iava at the time of our English mens being there". This was published in 1589.

Antonio Pigafetta himself compiled and incorporated into his narrative a list of 426 Malay, Bisayan and Tagalog words with their Italian equivalents. Some of these words were eventually published in French. Pigafetta's list is much more comprehensive and sophisticated than the others. He included words relating to Islam and to family relationships, the names for a wide range of textiles, spices, and metals, household terms, personal raiment, and the winds.

Pigafetta most likely used Henrique, the Malay from Sumatra as the source of his compilation. This is evident from the list of words which he published. The words were the common Malay current in the commercial centres of the East which was then called as the "language of Malacca". It was obvious that he did not learn the words from the peoples that he met in the journey.

One of the earliest known books filled with vocabulary and collection of Malay dialogues was written by Frederick de Houtman. His book entitled "Spraecke ende Woordboeck, inde Maleysche ende Madagaskarsche Talen" was published in Amsterdam in 1603.

Who was Frederick de Houtman? He was a Dutch explorer. When he was around 25 years old, he assisted a fellow Dutch navigator Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser with astronomical observations during his first expedition from Holland to the East Indies in 1595 to 1597. During subsequent expeditions he added further stars to the list of those observed by Keyser.

Houtman learnt the Malay language the hard way. He was imprisoned by the Sultan of Aceh in Sumatra for two years. However during those two years imprisonment he made good use of his time by studying the local Malay language and making astronomical observations. In 1603, after he returned back to Holland, Frederick de Houtman published his stellar observations in an appendix to his dictionary and grammar of the Malayan and Malagasy languages.

He studied the conversations of the people in Aceh and in that book he reproduced the conversations in both Dutch and Malay. His dialogues form one of the best useful guides to latter traders dealing in many important subjects such as the weighing of pepper and the purchasing of provisions. He also included all there is to know of how to drive a hard bargain and also how to extract debts from those who had not paid them.

In his book the Malay conversations were written and published in the 17th century manner. An example would read:

D. Essalemalecom, Ebrahim.

A. Malecom selam Daoet.

D. Derri manna datan pagi hari?

A. Beta datan derri pakan.

D. Appa achgabar? Tieda gabar batou derri barang Cappal?

A. Souda beta deng'ar beonji bedyl, iang itoe alamat derri Cappal dagang.

D. Lagi hamba deng'ar catta iang satoe Cappal derri Guiserat souda datan.

A. Appa pervinjaga de bava di'a?

In 1614 Augustus Spalding translated Houtman's book into English. Houtman's book now entitled "Dialogues in the English and Malaine languages" became the first Malay book to be published in English.

Many other Malay books were published later on in Europe but it was not until around the mid-17th century that the Dutch through their Dutch East Indies company headquarters in Batavia (today's Jakarta) that the printing presses there started to print books in the Malay world.

The Golden Legacy is the longest running column in The Brunei Times. The author also runs a website at bruneiresources.com.

-- Courtesy of The Brunei Times --

written by Rozan Yunos

published in The Brunei Times on Sunday, February 17, 2013

|

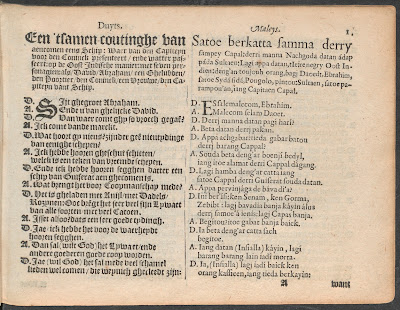

| A page from the first Malay book in Europe |

IN THE 16th century, European travellers and traders started arriving en masse at Southeast Asian trading ports. They wrote about the cities and the peoples whom they encountered.

Many of the descriptions about Brunei were derived during this period. Among the famous travellers was Antonio Pigafetta, the Italian chronicler who arrived in Brunei as part of Magellan's voyage circumnavigating the globe. Pigafetta's descriptions of Brunei are most often quoted nowadays. There were other travellers as well who were here in Brunei such as the Spanish, the Portuguese and the Dutch. The British and the Americans came much later.

Malay was then widely spoken in the region. In the 15th century, during the Malacca Sultanate, Malay was used as the regional language, a sort of lingua franca in the Malay archipelago. Malay was spoken by both the locals who live in this region and also by the traders and artisans that stopped and traded at Malacca using the Straits of Malacca. Around the Borneo Island and around the islands of southern Philippines and perhaps the northern Philippines, Malay must have been used as well.

Amin Sweeney in his book "A Full Hearing: Orality and Literacy in the Malay World" (1987) noted that European writers of the 17th and 18th centuries such as Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1605-1689), Louis Thomassin (1619-1695) and John Werndly (1656-1727) were describing the Malay language as the "language of the learned in all the Indies, like Latin in Europe". The Dutch scholar, Francois Valentijn (1666-1727) also described the use of the Malay language in the region as being equivalent to the contemporary use of Latin and French in Europe.

With the Malay language so widely used in Southeast Asia, many wondered how these Western traders communicated with the natives of Southeast Asia at that point in time.

Obviously, the first Europeans who arrived returned back with notes and perhaps compilation of vocabularies to help other latter traders.

Some perhaps had their own Malay interpreters among their crew. According to Donald Lach in the book "Asia in the Making of Europe: Volume II: A Century of Wonder Book 3" (1998), among the crews working for Magellan was a native Malay slave from Sumatera who Magellan had brought back to Europe much earlier. He was known as Henrique. When Pigafetta was in Brunei and in Southeast Asia, he had at his disposal this Henrique who was able to help him communicate with the peoples of Southeast Asia then.

However what probably helped the latter European traders was that a number of these notes and vocabularies collected and compiled by the early European traders were actually printed and made available to them.

Sir Francis Drake was the second person after Magellan to circumnavigate around the world. His squadron consisting of five vessels left in December 1577, and returned in September 1580 with only one vessel completing the journey. However, despite that setback, Sir Francis Drake's companions managed to compile a list of 32 Javan words with their English meanings. The compilers also provided a list of the "Kings or princes of Iava at the time of our English mens being there". This was published in 1589.

Antonio Pigafetta himself compiled and incorporated into his narrative a list of 426 Malay, Bisayan and Tagalog words with their Italian equivalents. Some of these words were eventually published in French. Pigafetta's list is much more comprehensive and sophisticated than the others. He included words relating to Islam and to family relationships, the names for a wide range of textiles, spices, and metals, household terms, personal raiment, and the winds.

Pigafetta most likely used Henrique, the Malay from Sumatra as the source of his compilation. This is evident from the list of words which he published. The words were the common Malay current in the commercial centres of the East which was then called as the "language of Malacca". It was obvious that he did not learn the words from the peoples that he met in the journey.

One of the earliest known books filled with vocabulary and collection of Malay dialogues was written by Frederick de Houtman. His book entitled "Spraecke ende Woordboeck, inde Maleysche ende Madagaskarsche Talen" was published in Amsterdam in 1603.

Who was Frederick de Houtman? He was a Dutch explorer. When he was around 25 years old, he assisted a fellow Dutch navigator Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser with astronomical observations during his first expedition from Holland to the East Indies in 1595 to 1597. During subsequent expeditions he added further stars to the list of those observed by Keyser.

Houtman learnt the Malay language the hard way. He was imprisoned by the Sultan of Aceh in Sumatra for two years. However during those two years imprisonment he made good use of his time by studying the local Malay language and making astronomical observations. In 1603, after he returned back to Holland, Frederick de Houtman published his stellar observations in an appendix to his dictionary and grammar of the Malayan and Malagasy languages.

He studied the conversations of the people in Aceh and in that book he reproduced the conversations in both Dutch and Malay. His dialogues form one of the best useful guides to latter traders dealing in many important subjects such as the weighing of pepper and the purchasing of provisions. He also included all there is to know of how to drive a hard bargain and also how to extract debts from those who had not paid them.

In his book the Malay conversations were written and published in the 17th century manner. An example would read:

D. Essalemalecom, Ebrahim.

A. Malecom selam Daoet.

D. Derri manna datan pagi hari?

A. Beta datan derri pakan.

D. Appa achgabar? Tieda gabar batou derri barang Cappal?

A. Souda beta deng'ar beonji bedyl, iang itoe alamat derri Cappal dagang.

D. Lagi hamba deng'ar catta iang satoe Cappal derri Guiserat souda datan.

A. Appa pervinjaga de bava di'a?

In 1614 Augustus Spalding translated Houtman's book into English. Houtman's book now entitled "Dialogues in the English and Malaine languages" became the first Malay book to be published in English.

Many other Malay books were published later on in Europe but it was not until around the mid-17th century that the Dutch through their Dutch East Indies company headquarters in Batavia (today's Jakarta) that the printing presses there started to print books in the Malay world.

The Golden Legacy is the longest running column in The Brunei Times. The author also runs a website at bruneiresources.com.

-- Courtesy of The Brunei Times --

Comments